Shino Glazes

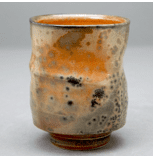

Shino glazes are a type of glaze known for their beautiful milky white to orange colors and fleshy textured surfaces. Originally developed in 16th century Japan, these glazes were used on tea bowls prized for their understated elegance. Eventually making their way to the United States, where a new era of shino glazes evolved.

Shino glazes in Japan have traditionally been white. Which is quite ascetic from the tans, golds and browns that many westerners association with shino glaze. It is not known where the name shino came from. Two theories persist, one being that it is a discombobulation of the word “Shiro” which means “white” or “whiteness. (Figure 1)

The other theory is that the glaze is named after a monk, named Shino Shoshin (1444-1523), who was fond of the glaze. No matter the origin of the name, the glazes are most common associated with the Momoyama Period (1568–1600) in Japan. More specifically in the Mino region of Japan, and to this day, you may hear the term “Mino Shino” referring to whiter shino variations.

Traditionally fired in anagama kilns using a reduction atmosphere, Shino glazes benefit from a long firing process with slow cooling. This unique firing method contributes to the glaze’s characteristics. Modern reduction firings can produce lovely shino glazes, although, slower cooling and possibly reduction cooling can help liven up their appearance. Although the most important factor, as always is understanding and making the most of their chemistry.

Understanding the Chemistry of Shino: Beyond the Surface

The key to achieving the Shino look lies in the glaze’s chemistry. Here’s a breakdown of the essential elements:

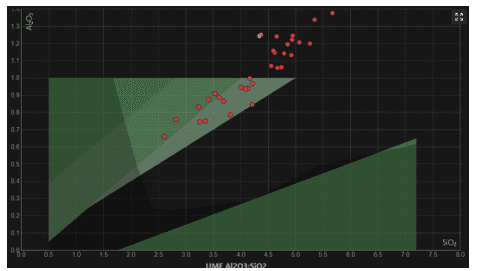

High Alumina: Low Silica: Shino glazes universally have very high Alumina levels, (0.7 or higher) and relatively low silica levels. Making the micro region on Stull’s map, appear in the highest parts of the “Matte” region and even extended beyond the established levels of the map. As we can see from this collective analysis of glazes from glazy.org . (Figure 2)

Sodium: Sodium, is imperative for the performance of shino glazes. Primary because the chemistry of shino glazes is different from that of other glazes. The vast majority of glazes use two different type of fluxes. Alkali Metal, from the curst column of the periodic table. And Alkaline earths, from the second column. Shinos only use the Akali Metal fluxes of the first column. More specifically Sodium, although many shino will use a lithium source. The sodium is both a powerful flux, but also aiding in the “flashing” and “Carbon trapping” associated with many shino glazes.

You will find materials like Nepheline syenite and soda ash, as concentrated sources of sodium for those purposes.

Iron: Even small amounts of iron in the clay or glaze can contribute to the orange flashes.

What Makes Shino Glazes Special?

Unique Aesthetics: Shino glazes are known for their crawling effect, where the glaze pulls away from the clay. While they have a characteristic white base, the exact colors and textures can vary depending on the iron content in the clay and glaze, as well as the firing process. Reduction firing, with limited oxygen in the kiln, plays a crucial role- particularly carbon trapping which creates dark shadowy areas.

However, some potters achieve similar effects through oxidation firing with adjustments to the recipe.

Connection to Wabi-Sabi: These glazes embody the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in imperfection and impermanence.

Western Shino Glazes

Western potters adopted Shino glazes in the 20th century, although the glaze evolved into their one aesthetic. Utilizing more soluble sodium, to induce flashing, carbon trapping, and the more golden colors that are associated with Shinos in the United States.

Wider Range of Colors: Modern potters may introduce colored frits or pigments to create a broader spectrum of hues.

Functional Glazes: Many potters today create Shino glazes with a more glossy, functional finish suitable for everyday use.

Beyond the Recipe: Techniques and Practice

While the recipe is important, mastering Shino glazes involves more than just chemistry. Techniques like glaze application thickness and firing schedules significantly impact the final outcome. Experimentation and practice are key to achieving your desired Shino effects.

Shino are known for crawling, because of their high feldspars and kaolin levels. Do your best to experiment with water content in your shinos and your application methods, to minimize crawling.

Understanding the science behind Shino glazes opens doors to exploration and experimentation. With a bit of knowledge and a willingness to practice, you can create your own unique pieces that capture the essence of this timeless ceramic tradition.

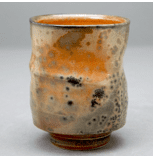

Examples of Shino Figure 3 and Figure 4

Want to Learn More? Join Our Community

Check out our podcast For Flux Sake Episode 68. Matt, Rose and Kathy discuss some of the history, science, and stunning beauty of these unique glazes.

Also, become part of our community of passionate ceramicists. Explore our online courses and workshops, follow us on social media @ceramicmaterialsworkshop, and sign up for our newsletter. Together, we can build a community of informed and empowered ceramic makers who value quality and craftsmanship.

Have a few more minutes? Check out our YouTube channel below for an overview of the Glazed and Confused course. We add new videos frequently, so make sure that you subscribe to be notified when we add new content.

-The CMW Team

Shino Teabowl with Bridge and House, known as “Bridge of the Gods” (Shinkyō)