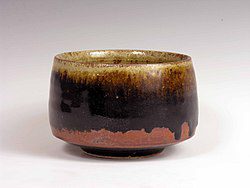

The Magic on the Surface: Common Tenmoku Types

- Hare’s-fur (nogime): Look for fine, vertical streaks that resemble animal fur. These are created by iron crystals stretching and growing as the glaze melts and flows.

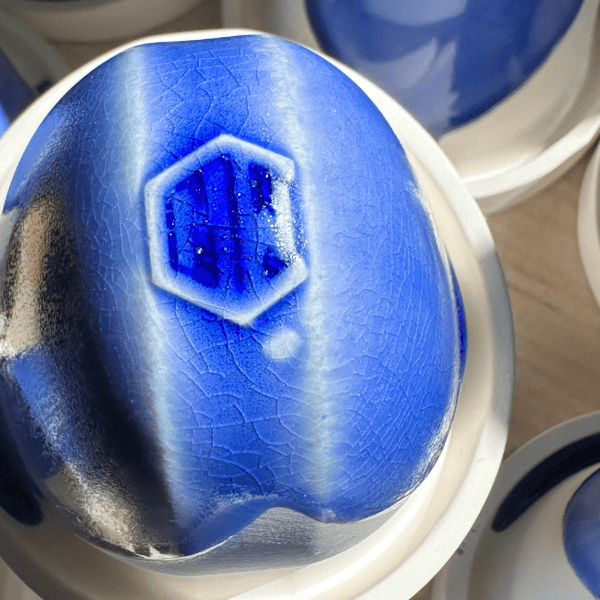

- Oil-spot (yuteki): These are gorgeous silver to iridescent spots that look like oil floating on water. Counterintuitively, these spots form when the iron-saturated glaze is fired in oxidation and often applied quite thick. The controlled firing schedule allows the iron to bubble up and crystalize on the surface, often requiring a short, hot soak or controlled cool to make those crystals really pop.

A Journey to the East: Where Tenmoku Comes From

The origins of this stunning glaze are deeply rooted in history. The look originated with Jian ware from Fujian, China, during the Song dynasty (12th–13th century). The name itself is a historical footnote: Japanese monks visiting Tianmu Mountain (which is pronounced “Tenmoku” in Japanese) brought the black-glazed bowls back to Japan. These imported bowls quickly became known as tenmoku—a direct tribute to the mountain. From there, Japanese masters in regions like Seto and Mino developed their own distinct tenmoku traditions.

I’m interested in exploring more glazes! You’re in luck! CMW just published about Fake Shino Glazes HERE!

Studio Success: Tips for Using Tenmoku Well

Working with this glaze family can be incredibly rewarding, but it has a few specific needs to look its best. Clay and Shape Tenmoku thrives on iron-bearing stoneware. Historically, it was almost exclusively used on bowl shapes—think tea bowls, yunomi, and serving bowls. Why? The rounded, pooling interiors allow the thick glaze to gather, deepening the color and enhancing the glossy shine. Curves are your friend!

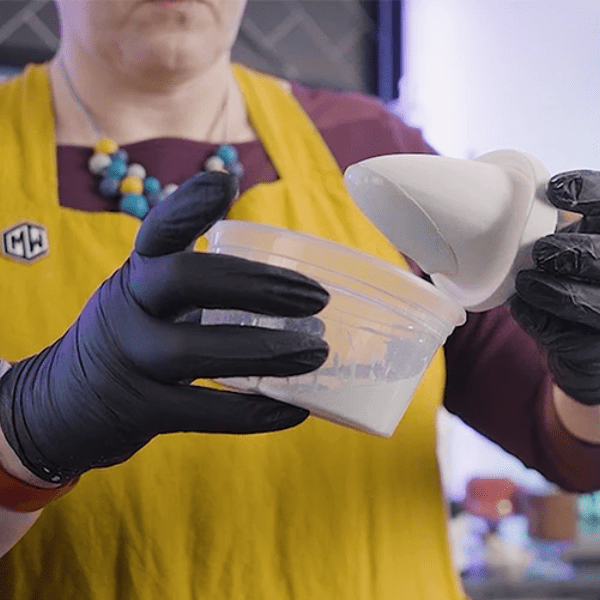

- Thickness: Go a touch thicker than you might with your celadons or shinos. However, watch for runniness! Iron is a powerful flux at high temperatures. Always use a clean foot ring and, if you’re pushing the thickness, a catch plate for safety.

- Classic Black-Brown: Achieve this with a reduction firing at high temperature.

- Oil-Spot Tenmoku: Fire this type in oxidation and apply it fairly thick. Many potters employ a hot soak and/or a controlled cooling cycle to ensure those spots crystalize perfectly. (While cone 6 versions exist, the most dramatic results come from cone 10 oxidation.)

It’s great inspiration if your own rim fires a bit dry!

Seeking Inspiration: Where to See Legendary Tenmoku

If you want to see the best examples, you’ll have to visit major art museums around the world. These institutions hold some magnificent pieces of Jian ware and its Japanese descendants:

- The Met (New York): Look for their Southern Song, 12th-century Tenmoku Tea Bowl with Hare’s-Fur Glaze.

- British Museum (London): They have a beautiful Jian hare’s-fur temmoku bowl that explicitly explains the Tianmu/Tenmoku name.

- Smithsonian, Freer Gallery (Washington, DC): They host Jian tea bowls, some of which feature those historic metal-banded rims.

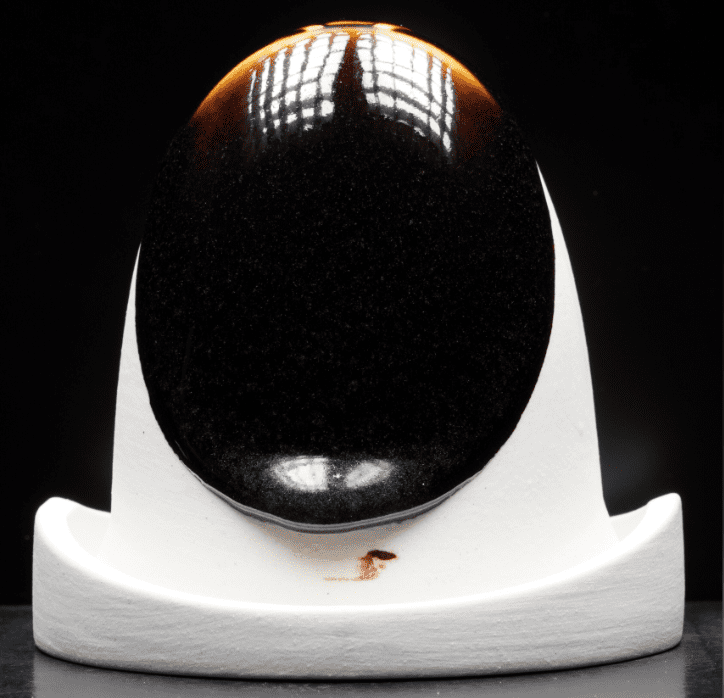

The Legendary Yōhen Tenmoku

The true “Holy Grails” of the ceramic world are the Yōhen (曜変) Tenmoku bowls. These are the iridescent, galaxy-like oil-spot masterpieces—and they are famously rare. Only three acknowledged examples exist, all preserved in Japan as National Treasures (at Ryōkō-in, the Fujita Museum, and the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum). Seeing one in person is a rare treat, as they are only occasionally put on public display.

Making Glazes, MAKE SENSE!

Unlock the mysteries of ceramic glazes with Making Glazes, Make Sense: The Ultimate Glaze Chemistry Guide, our most comprehensive glaze course to date! This isn’t just another glaze class; it’s the definitive guide to mastering glaze chemistry, designed for all levels of students – beginner, intermediate, and advanced learners are all welcome.

Ready to dive deeper?

Loved learning about ceramic glazes? Want to go even deeper? Check out our Workshops & Courses, now available in Spanish, or YouTube Channel where Matt breaks it all down, myth-busting and Stull chart included!